Improving patient safety

We all agree that communication in the operating room is essential. It saves time and ensures a better quality of patient care. Using the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist supports this. How can we learn to use this checklist?

Posted by

Published on

Tue 22 Oct. 2019

Imagine that it happens to you. You come out of the operating room and it seems that they have performed an operation that was not intended for you. Luckily, this happens only occasionally, it is not daily news.

But, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), the risk of a patient dying while receiving medical care is currently estimated at 1 in 300. This underlines the importance of learning to work well with checklists by healthcare professionals.

Checklists are the ultimate safety nets. You just have to be sure that the patient you are about to operate is the right one. You need to answer questions such as ‘is this the right patient’ and ‘what operation are we performing’, before reaching for your tools.

WHO checklist evaluation

Already in 2008, the WHO published guidelines identifying multiple recommended practices to ensure the safety of surgical patients worldwide. The WHO Surgical Safety Checklist is developed by professionals and is based on a core set of safety standards. It consists of three phases:

- Sign in, before induction of anesthesia

- Time out, before skin incision

- Sign out, before patient leaves operating room

The Checklist helps ensure that important safety steps are reliably followed for each operation.

Recently, the WHO updated the 10 facts on patient safety. They are quite shocking facts. Reasons enough to keep insisting that students and professionals should practice using checklists, keep improving teamwork and communications, and participate in simulation-based training. The AV recording tool Viso is very suitable for such a training.

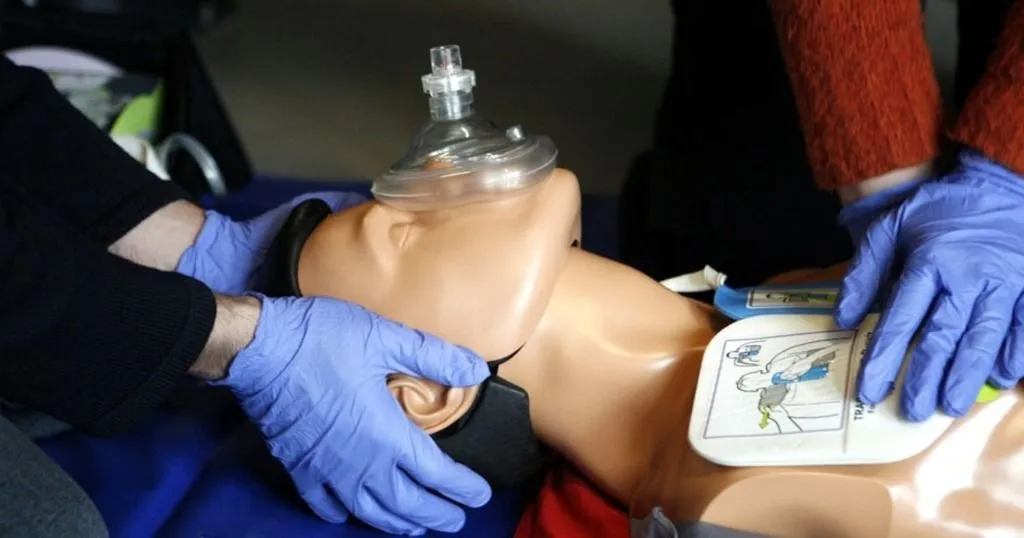

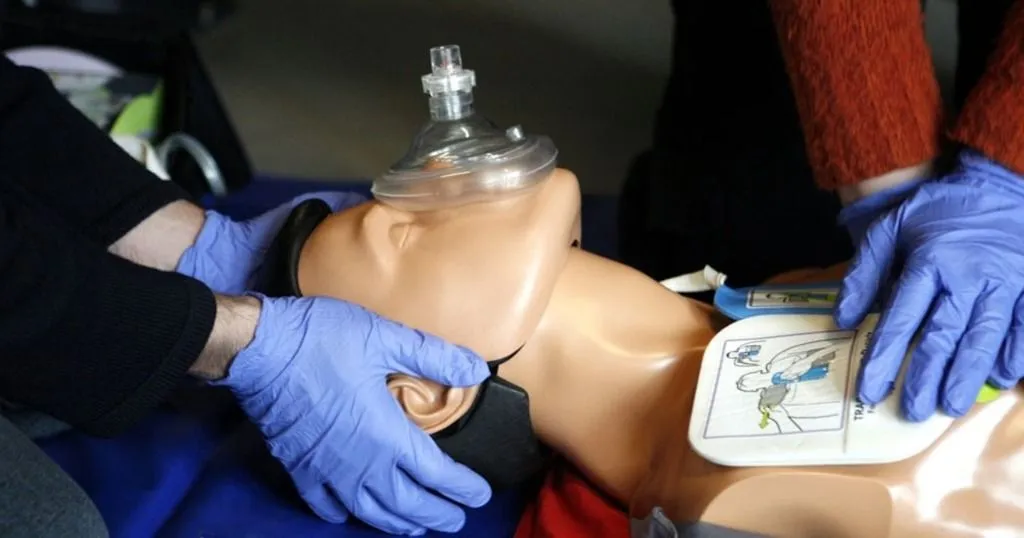

Simulation-based training to improve communication

One of the goals of the WHO checklist is to facilitate communication between team members. Medical professionals carry out their jobs with the utmost precision, but one of the biggest pitfalls is in the space between them—communication. A simulation-based training is suitable for training communication skills as well as using a checklist.

By recording the sessions and marking events of interest, which can be viewed afterwards, the team can discuss what went well and what did not. The lessons learned can be discussed during a more extensive debriefing.

Improving patient safety by observing behavior

Rydenfalt et al. (2013) evaluated the usage of the WHO checklist (version 1). The research team focused on the occurrence of checklist items in the Time out phase and identified several points for improvement. In order to analyze this phase quantitatively, Rydenfalt and colleagues recorded 24 surgical procedures using one camera in the operating room.

To accurately code behaviors, the researchers used The Observer XT software. They assessed whether participants engaged actively and coded the frequency in which items on the checklist occurred. Active participation was defined as “a team member having some input either by asking or by answering questions on the checklist”. Checklist items were then coded as performed or not performed.

Naturalistic observation studies

Regarding the chosen method, Rydenfalt et al. explained that “naturalistic observation studies can avoid the selective perception of participants and enable researchers to notice things that escape the awareness of the participants”. Although the results showed that the checklist was not always used as intended, the results also indicated that the Time out phase (step 2 in the checklist) was initiated in almost all surgical procedures.

The study also showed that team members sometimes conducted other professional tasks, unrelated to the Time out, during the Time out phase, such as throwing out trash or raising the operating table.

Communication in healthcare

Because introductions can promote trust amongst team members and encourage team building, they are a part of the checklist that should not be overlooked. However, the study showed that team members did not always introduce themselves.

Although it could be argued that team members already know each other from previous operations, this may not always be the case. When a stressful situation occurs, it may be too late to clarify names and roles of team members.

Stressing the importance of underlying processes

Rydenfalt et al. explain that it is important to describe ‘risk’ as what can and should be done to avoid risks that expose patients to danger and thus improve patient safety. All personnel should be aware of the risk-reducing intention of the checklist.

Additionally, risks are often linked to active failure, such as avoiding an incision in the healthy leg as opposed to the leg that requires surgery. However, risk can also be linked to communication failure.

Rydenfalt et al. state that “communication failures and the checklist items related to facilitating good and clear communication may be perceived by hospital personnel as being less significant”. They conclude that adherence to the checklist will most likely involve altering the staff attitude towards checklist items, thereby facilitating effective risk-reducing communication.

By addressing the importance of underlying processes, teamwork can be improved, thus positively influencing and increasing patient safety.

References

- Rydenfalt, C.; Johansson, G.; Odenrick, P.; Akerman, K.; Larsson, P.A. (2013). Compliance with the WHO surgical safety checklist: deviations and possible improvements. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 1-6.

- World Alliance for Patient Safety. WHO guidelines for safe surgery. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008.

Related Posts

Evaluating ergonomics in healthcare – paramedics

Operating room layout: impact on work patters and flow disruptions